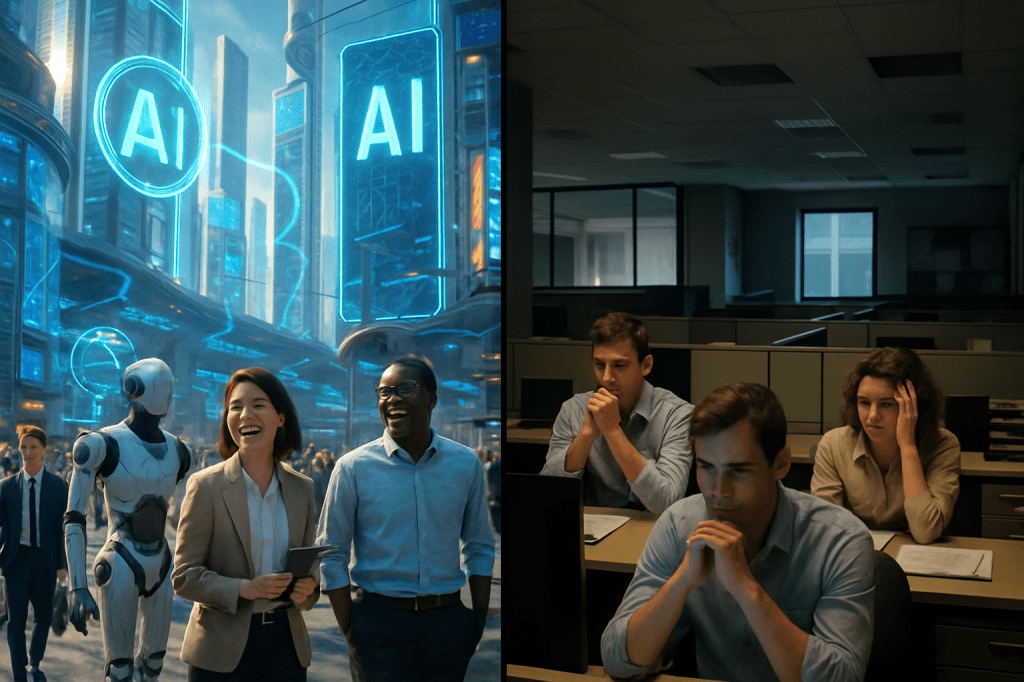

The architects of our AI future rarely agree on everything, but a recent public exchange between Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang and Anthropic CEO Dario Amodei laid bare a fundamental schism at the heart of the industry’s vision for human employment. This wasn’t a theoretical debate among academics; it was a direct clash between two of the most influential figures shaping AI’s trajectory, and their diverging predictions cast a long shadow over the white-collar workforce.

The Contending Visions

On one side stands Dario Amodei, co-founder of Anthropic, a company deeply invested in AI safety and alignment. His perspective, highlighted by Axios, is stark:

- He warns that AI could displace up to half of all entry-level white-collar jobs within the next five years.

- This rapid displacement, in Amodei’s estimation, could lead to an unprecedented 20% unemployment rate.

- His call is for transparency and proactive, systemic measures to mitigate this impending shock. It’s a plea for societal preparedness, acknowledging the scale of disruption his own creations might unleash.

Countering this sobering forecast is Jensen Huang, the visionary behind Nvidia, the company powering much of the current AI revolution. Huang’s stance is characteristic of a tech titan focused on growth and innovation:

- He posits that AI will create not just more jobs, but “better” jobs.

- Huang draws parallels to historical technological shifts, like the mechanization of agriculture, arguing that productivity gains historically lead to new forms of employment rather than net losses.

- His advice to the workforce is simple: adapt. Learn to leverage AI effectively, as it’s a tool for augmentation, not outright replacement.

- Crucially, Huang frames AI as the catalyst for a new industrial revolution, emphasizing the massive infrastructure build-out—think data centers and compute factories—that his company directly profits from. This isn’t just a philosophical argument; it’s a strategic one.

Beyond the Soundbites: What This Really Means

This isn’t merely a difference of opinion; it’s a fundamental divergence on the very nature of AI’s impact. Amodei’s concern targets a specific, vulnerable demographic: the entry-level white-collar worker. These are the roles traditionally seen as pathways into professional careers, often relying on structured tasks, data processing, and basic analysis—precisely the areas where current AI capabilities are excelling and rapidly improving.

If Amodei’s 5-year timeline for a 50% reduction in these roles holds true, the implications are profound. It suggests an economic bottleneck for new graduates and career changers, potentially exacerbating social stratification and making the “ladder” of professional advancement far steeper, if not entirely removed, for many. A 20% unemployment rate isn’t just a number; it’s a societal earthquake that would demand unprecedented governmental and educational responses.

Huang’s counter-narrative, while optimistic, carries its own set of challenges. “More and better jobs” implies a significant re-skilling imperative on a scale never before seen. The “better” jobs might be highly specialized, requiring advanced technical literacy or creative problem-solving that AI can’t replicate. The question then becomes: how many can make that leap, and how quickly? His vision of a new industrial revolution centered on AI infrastructure is undoubtedly happening, but the jobs created there, while significant, may not directly absorb the millions displaced from other sectors.

The core tension here is speed versus adaptation. Amodei sees a tidal wave hitting before society can build adequate defenses. Huang sees a rising tide lifting all boats, provided they learn to sail. For those of us already watching AI reshape our professional lives, this debate isn’t abstract. It’s a stark reminder that the very leaders building this future have wildly different expectations for its immediate human cost. The time for passive observation is long past; the real question is which of these futures we are actively preparing for.