The Quarter When Companies Hired Servers Instead of People

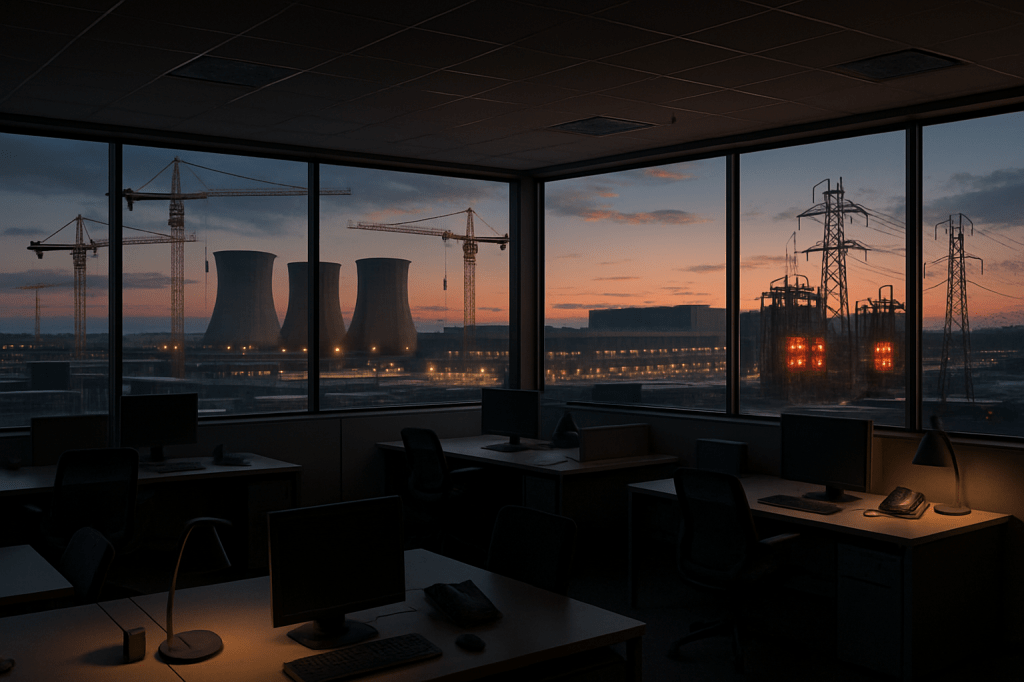

Across corporate America, the hiring button is dim while the procurement cart overflows. Axios put crisp language to the pattern executives have been whispering for months: cash is flowing into AI and digital infrastructure—data centers, software, and the tools that tie them together—while headcount growth stalls and raises lose momentum. If the economy feels like a split-screen—record stock indexes sharing the frame with a cooling job market—it’s because the engine under the market’s hood isn’t payroll; it’s capital spending on computation.

Look at the seams where growth usually lives. Unemployment sits at 4.3%, yet average monthly job gains from May through August hovered around 27,000—a fraction of last year’s pace. The New York Fed finds workers’ confidence about landing a new job at a series low. In boardrooms, the mood is even clearer: a Business Roundtable survey shows more large-company CEOs planning workforce reductions over the next six months than expansions, while almost nine in ten expect capital expenditures to stay steady or rise. The GDP math whispers the same story—spending on information-processing equipment and software contributed more to growth in the first half than consumers did. The country is building a new production stack.

Neel Kashkari offered the most concise explanation: “While it takes a lot of people to build a new data center, it takes relatively few to operate one.” That single sentence reconciles buoyant equities with soft job creation. Firms are buying future margins. The operating model after deployment is leaner per dollar of revenue, and investors are paying up for that glide path today. Jerome Powell, asked whether AI is chilling entry-level hiring, allowed it “may be” part of the story—an unusually direct nod from a Fed chair that the labor market’s weak spots are not only cyclical.

The corporate calculus has changed

In the old playbook, a CFO weighed a hiring plan against incremental software licenses and declared victory when revenue per employee improved a couple of points. In the new one, the comparison is between a pay raise that preserves capacity and an AI stack that expands it. If a foundation model plus process rewiring yields a step-change in throughput, the spreadsheet wins before the first offer letter is drafted. This doesn’t just nudge the budget; it rewrites sequencing. Companies freeze net-new roles, stand up internal AI platforms, and then reintroduce hiring downstream only for the roles that complement the new system. That timing shift alone can produce a year where profits climb even as payrolls don’t.

There’s an uncomfortable micro detail inside the macro headline: the rungs that teach beginners how an industry works—entry-level operations, support, routine research, first-draft analytics—are exactly the tasks AI now handles at acceptable quality. Those rungs are not “gone,” but they are thinner, and they increasingly sit inside tooling rather than job descriptions. Without deliberate transition pathways, fewer apprenticeships become fewer mid-career experts five years from now. That is how a temporary hiring pause morphs into a skills pipeline problem.

The policy lens: a supply upgrade with employment risk

Two days before this Axios piece, the Fed cut rates and flagged rising downside risks to employment. AI complicates that backdrop. A wave of automation investment acts like a supply upgrade: it can expand potential output and, in time, cool inflation pressure. But it also loads adjustment costs onto specific workers and places. The analogy Axios invokes—the “China shock”—is not about AI’s global competition so much as its distributional math. The build phase concentrates jobs in a handful of counties hosting power, land, and fiber. The operate phase spreads benefits across balance sheets and software teams, not across entire local labor markets. Regions heavy in back-office, customer service, and routine cognitive work will feel the ache before the gains arrive.

For the Fed, that means classic guideposts wobble. If Okun’s law weakens because output rises without commensurate hiring, unemployment can drift up even while productivity quietly improves. Rate cuts intended to cushion labor may coexist with a capex boom that the same cuts inadvertently fuel. This is not a contradiction; it is the texture of a transition where capital substitutes for tasks faster than workers can move to the tasks AI amplifies.

The clock that matters

Everything now turns on speed. If AI-driven productivity shows up in realized output quickly, companies will have the revenue space to reopen headcount and the political space to argue the transition was worth it. If it lags—because data is messy, workflows are stubborn, or governance slows deployment—then we’re left with the worst mix: hesitant hiring, tepid wage growth, and capex that hasn’t yet paid for itself. The softness in job creation is the down payment on a promise of efficiency; the economy will demand the receipt.

The signals to watch are hiding in plain sight. Construction intensity around data centers will ebb as facilities turn on; at that moment, do operating metrics—output per hour, service throughput, defect rates—show the step-changes the spreadsheets forecast? Do corporate earnings calls shift from “pilots” to “productivity attribution,” with fewer anecdotes and more baselines? Do job postings rebound, but skew toward roles that orchestrate models and data rather than do the first draft themselves? And most telling for households: do wage gains reaccelerate for workers in AI-complementary roles while graduates entering formerly routine tracks continue to face thin demand?

Axios called this the “1 big thing” because it finally ties the market’s exuberance to the labor market’s chill without resorting to mysticism. The economy isn’t broken; it’s being rewired. The near-term bargain corporate America is making is clear: invest in intelligence, defer headcount. Whether that choice feels like prosperity or precarity depends on how fast those investments convert into broad-based productivity—and how quickly displaced workers can cross the gap to the jobs that AI makes more valuable instead of redundant.