The Fed Just Rewrote the AI Layoff Story: It’s the Term Premium, Not the Chatbot

On a Minneapolis stage built for tech bravado, the most provocative line about artificial intelligence was an exercise in restraint. Neel Kashkari, the Minneapolis Fed president who usually prefers plain talk to hedged prose, looked out at an audience primed for tales of imminent job loss and said, in effect: not yet. He didn’t deny the corporate whispers of AI-enabled hiring freezes. He simply reminded everyone that diffusion takes time, and history is unkind to forecasts that skip the messy middle between demo and deployment.

The headline wasn’t his skepticism about layoffs, though. It was where he redirected the conversation. Instead of reading AI as a story about immediate worker displacement, Kashkari framed it as a capital cycle with monetary gravity. The boom in data centers—and the power, land, grid upgrades, memory, networking, and debt that follow them—doesn’t just show up in tech earnings. It shows up in the bond market. Even if the Fed trims its policy rate, the heavy financing demand created by the AI build-out can keep longer-term borrowing costs stubborn, tugging up mortgages and other rates that decide whether a hiring plan actually becomes a headcount.

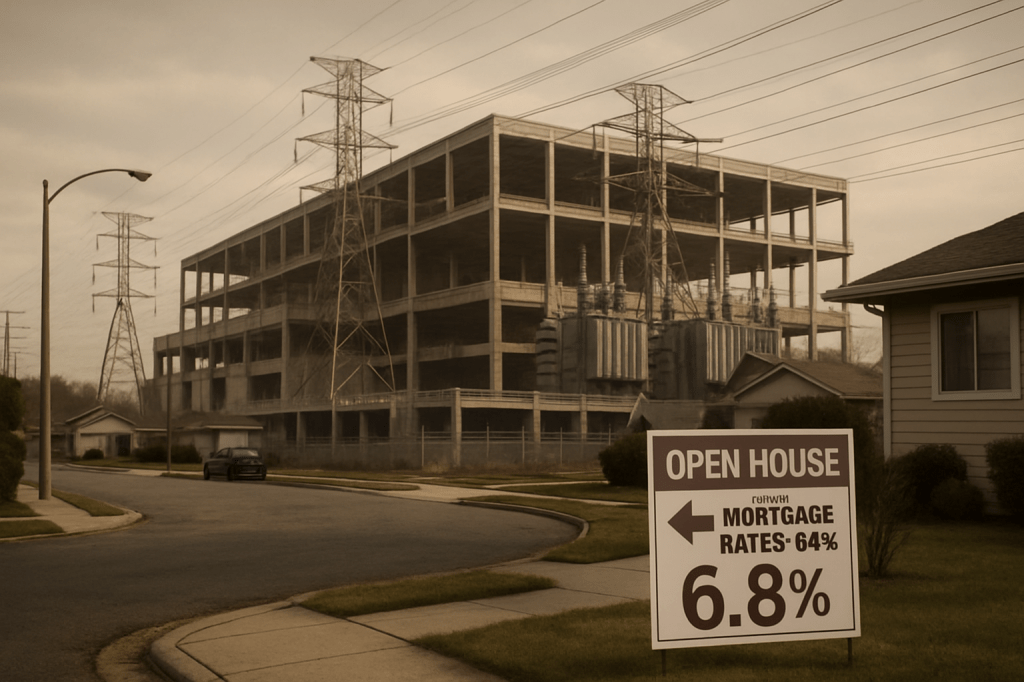

That pivot matters because it’s an inversion of the usual AI anxiety. The threat, in this telling, is not a model sitting down at your desk; it’s the cost of money reshaping where jobs get created. When capital chases data centers, other sectors wait their turn. Homebuilders see buyers balk at six-handle mortgages. Auto dealers watch monthly payments stretch. Small firms doing real-world automation—a robot arm in a warehouse, a CNC upgrade in a factory—look again at the financing terms and decide to sweat assets a little longer. Fewer requisitions go out. New roles get “approved pending rate environment.” The layoff narrative becomes a slow bleed in job creation, not a headline-grabbing purge.

Kashkari’s view aligns with a pattern economists know but rarely headline: investment booms raise the economy’s appetite for savings. When the private sector’s demand for long-duration capital jumps, the price of that capital—the long-term interest rate—can drift higher even as the central bank gently lowers the short end. Call it a private-sector crowding out, with AI data centers standing in for the usual suspect of deficit spending. The term premium thickens. Mortgage rates don’t follow the Fed down the staircase; they take the elevator only partway and then pause in the lobby.

None of this absolves AI of labor effects. Companies are already using the moment to hold headcount flat, replace attrition with software, and redesign workflows in ways that won’t show up in the data for quarters. But Kashkari’s reminder is that adoption lags are real. Productivity gains often arrive on a J-curve: first comes the capex and reorganization, then, after a delay, the measurable output. In the interim, the most visible jobs channel is indirect—financing conditions that squeeze rate-sensitive hiring while AI-centric firms hoover up engineers, electricians, and power project managers.

The policy subtext was just as pointed. Kashkari backed the September quarter-point cut and signaled he favors a couple more to protect the labor market. Yet he warned against over-easing into an economy where AI’s capital hunger could keep demand taut. And he was explicit about misattribution: whatever softness you see right now in the job market, look first to tariffs, not transformers and GPUs. It was a message delivered with on-the-record clarity in the Twin Cities’ biggest newsroom—and therefore meant to travel.

The upshot for anyone tracking who gets “replaced” next: watch the yield curve as closely as the product roadmap. If Kashkari is right, the choke point for employment in the near term is not a breakthrough model but the financing costs created by building the infrastructure to run it. That doesn’t make the human impact gentler. A job not posted because the mortgage market didn’t budge feels the same as a job automated away. The cause, however, points to different defenses: balance sheets, not résumés; grid interconnects, not prompt libraries.

AI’s labor story will eventually arrive in the office suite and the back office. Today, its first act is breaking ground in exurban lots and power corridors—and quietly editing the economy’s hiring script via the bond market. If you were waiting for a robot to take your role, note the twist. AI didn’t replace you this week. The data center did, by replacing your future employer’s borrowing capacity.