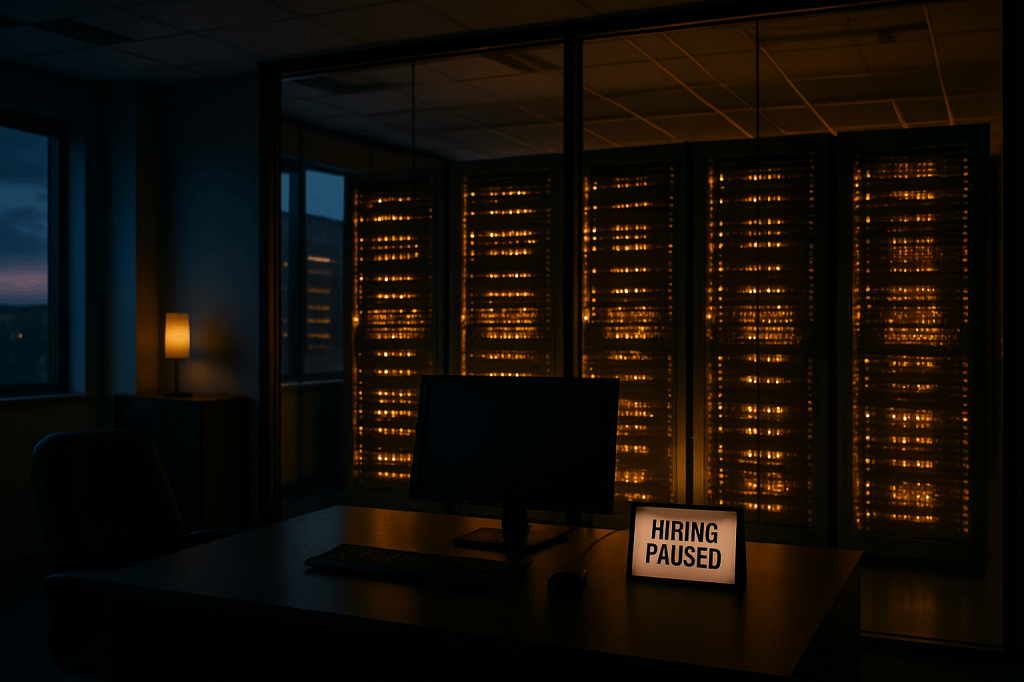

When the Fed put AI on the risk dashboard

Jerome Powell doesn’t usually narrate the future of work. He measures it. But this week, in the ritual after the rate cut, the Fed chair broke character. He described CEOs pressing pause on hiring, some moving to layoffs, and he named the reason they give when the cameras aren’t rolling: AI. Then he added the line that detonated beyond the bond market—after adjusting for likely overcounting, “job creation is pretty close to zero.” Fortune turned that moment into a megaphone, and suddenly the central bank wasn’t just watching inflation and growth; it was openly tracking automation as a channel of labor-market deterioration.

From company talking point to macro variable

Until now, the AI-and-jobs story lived in earnings calls and HR memos. A CFO would hint at “efficiency programs,” a CTO would talk about copilots, and somewhere a recruiter would be told to slow walk offers. Powell pulled those threads into the macro tapestry. He spoke of “a significant number of companies either announcing that they are not going to be doing much hiring, or actually doing layoffs,” and underscored that “much of the time they’re talking about AI and what it can do.” That’s not a forecast; it’s a translation of guidance the Fed hears from the biggest employers in the country. When the messenger is the institution calibrating interest rates for the entire economy, a micro narrative becomes a macro risk.

A labor market that looks fine until you touch it

On the surface, the unemployment rate sits at a still-low 4.3%. Underneath, Powell described a softer underbelly: a job-finding rate for the unemployed that is unusually weak, and headline hiring that may be flattered by statistical noise. The phrase “pretty close to zero” is a warning about momentum, not just levels. It suggests a market that can’t absorb displaced workers quickly, even as official layoff statistics lag. That friction is exactly how an adoption shock feels in real time—few pink slips today, but fewer doors opening tomorrow. The Fed cut rates by 25 basis points, citing “downside risks to employment,” not because AI alone is breaking the wheel, but because the wheel is losing traction where it matters.

The paradox of investment without headcount

Powell did not paint AI as a bubble. He noted that today’s leaders “actually have earnings,” and AI-linked capex is propping up growth. That’s the unsettling twist: the investment boom is labor-light. Firms are pouring money into compute and models while signaling headcount won’t grow “for a number of years.” In plain terms, productivity gains are arriving through capital deepening, not through adding workers. The economy can clock decent output with fewer hires, and that’s how you get the K-shaped feel Powell hinted at—profits and spending on one branch, tepid job creation on the other. If this pattern persists, the classic playbook—tight market begets wage pressure begets inflation—gets rewritten. Wage heat cools without a spike in layoffs, because companies replace marginal roles with software before a downturn forces their hand.

When the Fed says it out loud, incentives change

Central banks don’t just measure; they define what the cycle is about. By naming AI as a factor in hiring freezes and by tying it to a near-zero pace of job creation, Powell gave boards and investors a new baseline. CFOs can justify longer hiring pauses as “aligned with Fed-acknowledged dynamics.” Workers can no longer assume a low unemployment rate guarantees quick re-employment. Policymakers can justify easing even while capex hums, because the labor channel—the one that anchors the mandate—is weakening. In practice, this means the path to lower rates may be paved not by a recessionary spike in layoffs, but by a quiet spread of non-hiring.

The new cycle to watch

The tell won’t be in spectacular layoff headlines; it will be in slow metrics: the job-finding rate refusing to lift, hours worked inching down, temporary help remaining soft, and the gap between capital spending and payrolls widening. It will be in earnings calls where executives stop couching AI as an “assistant” and start describing entire workflows that no longer require a requisition. And it will be in the policy language that follows. The Fed is “watching that very carefully” because, for the first time in a long time, the most important labor-market story may be a supply-side revolution that lowers inflation risk while lowering opportunity at the same time.

Fortune didn’t overreach by calling it out; it amplified the structural shift embedded in Powell’s words. AI is no longer a sector story or a slide in a product keynote. It’s now part of the variable set that moves rates. If job creation really is hovering near zero once you strip out the noise, then the defining question of the next year isn’t whether AI is “good” or “bad” for jobs—it’s whether an economy can grow into a productivity boom fast enough to keep workers moving, or whether we are entering an expansion where the machines do the hiring and the people wait for the next opening that never gets posted.