The Beige Book’s Quiet Sentence That Redrew the Hiring Map

Some turning points arrive not with a chart-breaking print, but with a sentence slipped into an otherwise familiar document. In the Federal Reserve’s November Beige Book—released November 26, compiled by the Dallas Fed, and stitched from conversations held through November 17—one line surfaced that Fortune flagged a day later: a few employers said artificial intelligence had replaced entry‑level roles or lifted productivity enough to pause new hiring. It is an unassuming formulation, almost apologetic in its modesty. Yet the implications run straight through how modern companies staff up, how workers climb the ladder, and how the U.S. central bank reads the temperature of a labor market that feels cool to the touch even as the thermostat insists the furnace is still on.

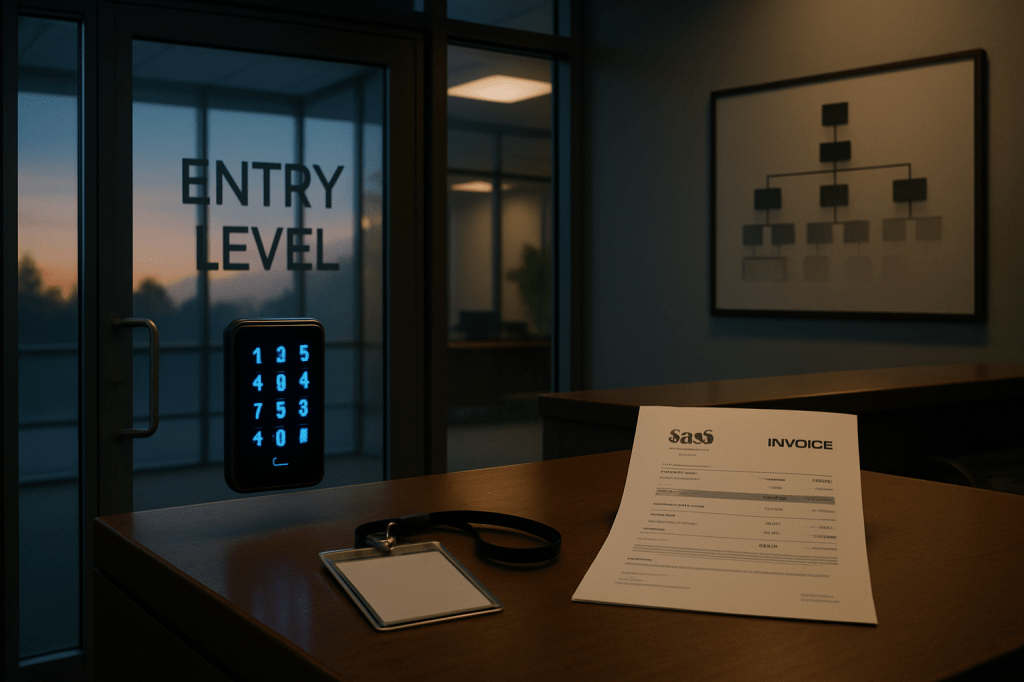

The Beige Book has always been an exercise in disciplined listening. This month, what it heard coalesced into a recognizable pattern: employment “declined slightly,” about half of the Fed’s districts saw softer labor demand, and firms managed headcounts with hiring freezes, backfilling only through attrition, and in some cases trimming hours rather than issuing pink slips. That “low‑hire, low‑fire” stance explains the dissonance workers have been reporting for months. Layoff headlines are fewer than feared, but opportunity seems to have slipped behind a glass panel. The panel, it turns out, is not empty air; it’s software.

The job that never appears

When a company replaces a role with AI, there is rarely a press release. There is simply a requisition that never gets written. The Beige Book’s new sentence dignifies this missing job with a name. AI is not just eliminating tasks inside existing roles; it is dissolving the entry point itself. That is a critical distinction. Traditional displacement sparks outrage and data—announced layoffs, severance, recall rights, and headlines. Suppressed openings, by contrast, hide in silence. Attrition absorbs departures. Hiring managers stretch teams a little further, then a little further again. Overnight, “we’ll train a junior” becomes “let’s prompt the model.”

This is where the central bank’s anecdote matters. It is not one company talking its book. It is a cross‑section of districts, industries, and pay philosophies yielding a consistent pattern: when demand softens, firms have three levers—freeze, replace only, or cut. AI has become a fourth lever that magnifies the first two. The headcount stays flat; the output doesn’t. On paper, that looks like gentle normalization. In the corridors where careers begin, it looks like a locked door.

The broken rung problem

Entry‑level jobs are not only a labor input; they are a teaching function. They subsidize inexperience with time, feedback, and repetition. Replace that rung with a tool and two things change at once. First, you remove the training ground where people develop into mid‑level contributors. Second, you reassign mentorship bandwidth to overseeing automation instead of onboarding humans. The result may feel efficient this quarter and expensive in three years when there are too few mid‑career candidates who have touched the messy edge cases that never made it into the data. A pipeline can look healthy from a distance; starve the intake and the pressure loss shows up later in surprising places—compliance failures, brittle product quality, stalled internal mobility, and wage spikes in the pockets where human judgment remains the bottleneck.

Investors will cheer the near‑term margin math. Executives will point to productivity wins that help them dodge layoffs and keep culture intact. But for workers, especially those without elite credentials, the bargaining chip was always the promise of learning-by-doing. If the doing is automated, the learning migrates to whoever controls the system, the dataset, and the exceptions queue. That is not simply a labor market story; it is a social mobility story, rewritten in the passive voice.

Macroeconomics in the negative space

The Beige Book’s language is careful. “A few firms.” “Slight decline.” None of this announces a slump. Yet the configuration—slower labor demand across roughly half the districts; headcount guarded through freezes, attrition, and hours; AI cited alongside those levers—helps decode the paradox of the moment. If AI is holding output steady with fewer new hires, then the economy can post respectable production without the churn that normally accompanies growth. Layoffs stay subdued, wage pressures ease from the edge, and the headlines suggest calm. But the lived experience for job seekers is more constricted, because the slack is being created at the mouth of the funnel rather than at the exit. Opportunity shrinks without the spectacle of a crisis.

For the Fed, that texture matters. A labor market that cools through suppressed openings rather than job cuts carries a different political and inflationary resonance. It alleviates some wage‑price pressure—fewer bidding wars for junior talent—without the scarring that follows broad layoffs. But it also dampens dynamism. New matches are where skills realign with technology and where young workers absorb institutional knowledge. If the economy leans too hard on “no new seats,” we get stability now and fragility later, the kind that doesn’t show up until an exogenous shock demands rapid hiring and the bench is thin.

Accounting for the job that isn’t a cost

There is a measurement puzzle embedded here. The tools that do the work of entry‑level employees are not booked as headcount; they are licenses and services buried in operating expenses. A manager cutting a role and spinning up a model is not flagged in the same way that a layoff is. That invisibility distorts the signals we use to steer policy, career choices, and education. Guidance counselors read job postings; CFOs read productivity dashboards; the Fed reads district anecdotes. When those three panes show different realities, misallocation follows.

The Beige Book does not resolve the puzzle, but it acknowledges it. By putting AI on the same line as hiring freezes and hours reductions, it effectively upgrades “automation as HR policy” from a quiet experiment to a recognized tactic. That is a threshold event, not because it is numerically dominant—it is not—but because it codifies a legitimate play in the corporate playbook. Once a tactic is legitimate, it spreads in meetings long before it shows up in statistics.

Where the curve bends from here

Two practical questions flow from this month’s narrative. First, when demand rebounds, do firms reopen the entry door or scale the tool? The answer depends on whether the last year’s pilots produced dependable workflows that managers trust. If they did, today’s “few” becomes tomorrow’s default. Second, which sectors convert the ladder fastest? Routine analysis, low‑stake drafting, basic support tasks—these were always the first candidates. If their conversion intensifies, the remaining human entry points will cluster in roles that either require in‑person presence or guardrails that models can’t yet cross. That narrows the geography and the credentials of who gets a start.

None of this is an argument that AI is bad for jobs in the aggregate or that the Beige Book heralds a cliff. It is a recognition that the path of least resistance for cost‑conscious firms in 2025 is to hold headcount flat and let software do the marginal work that a junior would have done. That is how a labor market can feel tighter for newcomers even as most incumbents stay put. It is how economic narratives can report calm while inboxes return more rejections that say “we’re not hiring right now” instead of “we’re going in a different direction.”

The beauty and the hazard of the Beige Book is that it captures the economy as people run it, not as models would prefer it to be. This month, the people quietly said they’ve found a way to save money without triggering headlines. They didn’t cut; they just didn’t add. And for the first time, the central bank wrote down what filled the gap.