The most valuable credential in the age of models isn’t from the cloud

At 7:12 a.m., a plumber in a salt-dusted van taps a tablet, checks a route the dispatch AI has already optimized, and heads toward a basement that won’t stop flooding. Across town, a marketing specialist stares at a dashboard that now drafts copy, targets segments, and schedules campaigns better than she can on her best day. One of these workers is about to be “augmented.” The other is about to be replaced.

Yesterday, Gene Marks spelled out the uncomfortable logic in the Guardian: if you want durable job security as AI spreads, get a state license—any state license. His column lands with the thud of common sense we’ve been trying to ignore. LLMs are crushing the text-and-spreadsheet layer of the economy. Robotics is improving, but physics, proximity, and permission still rule vast swaths of work. Licenses sit at the intersection of all three.

Why this argument bites now

We’ve spent two years counting white-collar layoffs as chat systems ate tickets, drafts, reconciliations, and “first passes.” Meanwhile, the quiet data points have been marching in the other direction: trade schools filling up since 2020, private equity rolling up HVAC and home services because the cash flows look like utilities, and a steady, decades-long expansion of licensure as consumers gravitate to vetted providers. Marks doesn’t pretend licensing is perfect policy—there’s a real, ongoing backlash against boards that overreach—but he’s blunt about its practical edge. A license is a state-backed signal wrapped around competency, liability, and the right to charge. It authorizes you to pull permits, sign off on work, and be the human the inspector or insurer expects to see.

That’s the part we often miss when we discuss “AI replacing X.” Replacement doesn’t happen in a vacuum; it happens inside systems of trust and regulation. A model can draft the electrical plan, but someone has to put their name on the work, interpret the weirdness inside an old wall, and carry the legal responsibility. The economics follow the signature.

The moat is physical, local, and regulated

The strongest claim in Marks’s piece is also the most actionable: anchor yourself where AI cannot act alone. That usually means hands-on, locally delivered, regulation-tied tasks—electricians, plumbers, home inspectors, nurses, beauticians, appliance repair, remodelers. Robots will increasingly handle the hazardous and the repetitive, and software will handle the paperwork and the quoting. But the human operator remains the center of gravity. Even in professions already absorbing AI—accounting is Marks’s own example—the machine chews through prep and analysis while the human earns the fee in judgment and counsel. The work changes; the worker stays.

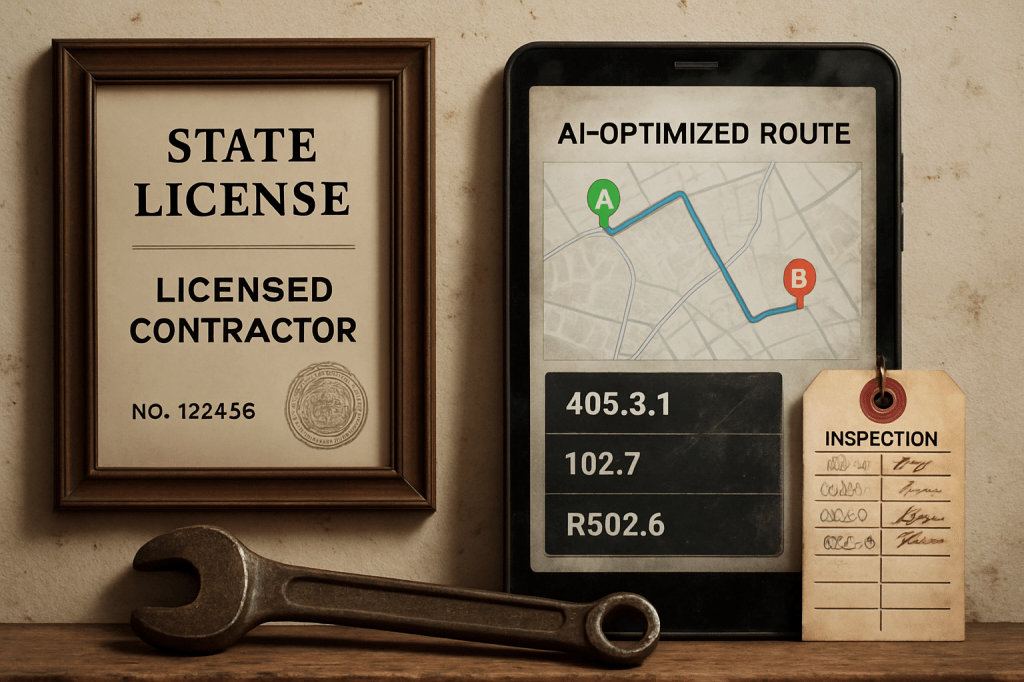

Notice how different this is from the old career advice. We used to tell anxious college grads to orbit the software industry, to chase titles that sounded future-forward. Now the competitive edge looks like paperwork from the statehouse. Not because it’s romantic, but because it creates bargaining power. It is portable across employers. It opens a path to “hang out a shingle” and price your time. And it composes cleanly with AI: the model drafts your estimate, checks code references, and schedules your day, while you turn the wrench, make the call, and take the liability.

AI will reshape licensed work—by making it more valuable

Spend ten minutes with a modern electrician and you can see the stack forming. Vision models find heat anomalies before the panel fails. Copilots build materials lists, map code updates to specific jobs, and write clean invoices that actually get paid. Drones do the attic crawl so the human doesn’t. Nurses triage with decision support systems that surface edge cases without slowing the line. Inspectors walk roofs with computer vision documenting every shingle. The result is not fewer licensed workers; it’s licensed workers with higher throughput and fewer headaches. If you hold the credential, AI is an exoskeleton. If you don’t, it’s a competitor that doesn’t need a desk.

The capital markets have already voted. When private equity buys neighborhood service companies, they are not betting on nostalgia. They are buying a regulated bottleneck with durable demand, then layering software to squeeze out scheduling slack, inventory waste, and quoting friction. In other words, they are institutionalizing the exact AI complement Marks describes. The margin lives in the license; the scale lives in the stack.

The politics are messy; the strategy isn’t

Yes, some licensing regimes go too far. Some protect incumbents more than consumers. Several states are trimming boards, experimenting with reciprocity, or sunsetting needless requirements. All of that debate is warranted. It doesn’t change the near-term calculus for a worker staring at accelerating automation. Until the policy rewrites actually arrive, licensure remains one of the few ways an individual can buy insulation from substitution and gain leverage over their own time.

The rewrite of career advice

Marks’s column reframes the AI-and-jobs conversation with refreshing specificity. Forget the vague promise of “AI jobs.” Pick a domain where the world still resists abstraction, pass the exam, and let the models do everything around the edges. If you’re mid-career and unlicensed, the shortest path to security may run through a community college, a state test, and a cheap printer for your business cards. If you are licensed already, the play is to adopt AI faster than your peers—turn documentation, diagnostics, scheduling, and compliance into background tasks, and spend your time on the human work clients actually value.

The most telling image from yesterday’s piece isn’t a robot or a dashboard; it’s a certificate on a wall. In an economy reorganized by AI, the moat is not mystery—it’s permission. And right now, permission still belongs to people.