The Weekend Warning That Put a Clock on AI’s Labor Shock

On a quiet December Saturday, an argument many of us have felt in our bones acquired a timeline and a name. London Business School’s Ekaterina Abramova didn’t just say AI is coming for jobs; she said it will come so quickly, and across so many desks at once, that the labor market’s usual shock absorbers won’t catch. Syndicated widely across Yahoo and AOL from Business Insider, her analysis traveled farther than most academic warnings do on a weekend. By nightfall, the phrase “historic labor shock” was everywhere, and the story hardened into the day’s central narrative about work: our risk is not inevitability, but velocity.

Abramova’s thesis cuts against the comforting rhythm of past transitions. Industrial mechanization marched sector by sector, an assembly line of displacement that—however painful—offered time to reassign skills and redesign institutions. General-purpose AI does not consent to that choreography. One frontier model can touch accounting checklists in the morning, debug code by lunch, and handle customer escalations by dinner. The churn isn’t moving factory to factory. It is moving task to task, horizontally, wherever a screen mediates value. That simultaneity makes entry-level analysts, junior developers, and support staff the first line of impact, not because they’re unimportant, but because their tasks are the easiest to abstract and automate.

The labor-market framing that landed hardest came by way of Lazard CEO Peter Orszag: labor markets handle small shocks delivered quickly, or big shocks delivered slowly—not big shocks that happen quickly. It is a simple taxonomy that turns the current debate on its axis. Whether AI ultimately produces more jobs than it destroys becomes a secondary question if the adjustment window is too narrow for people to stay housed, insured, and employable. Abramova’s window—five to ten years during which layoffs could outpace new-job formation—conjures a future that is not post-work, but post-patience.

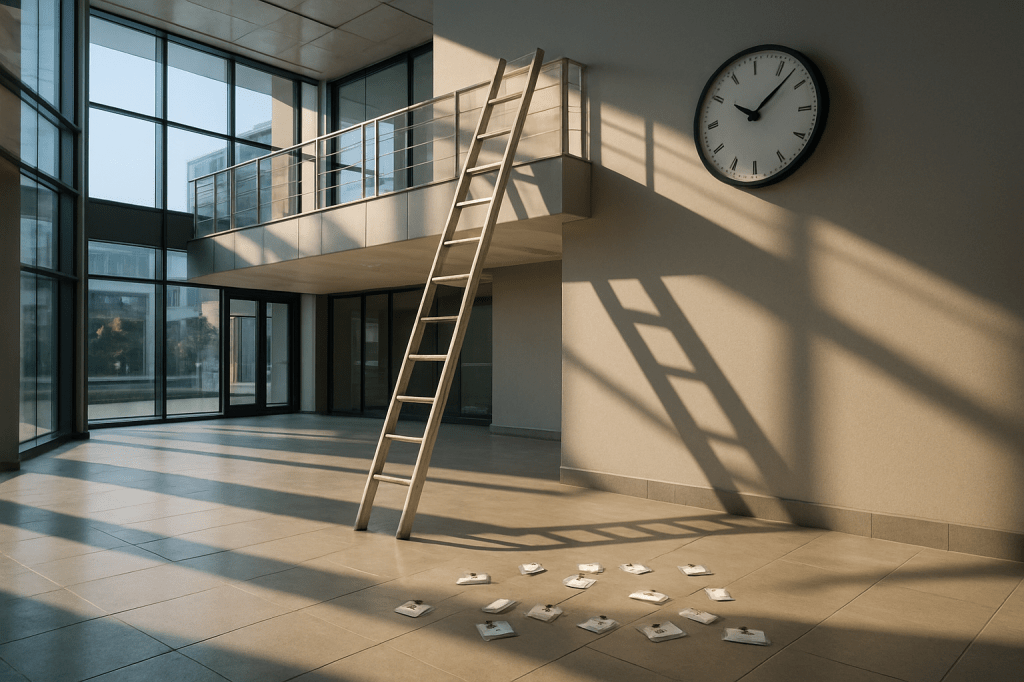

Her historical analogies gave the argument texture. The Enclosure Acts redrew livelihoods faster than communities could adapt; coal closures in the 1980s hollowed out towns in clusters, not at random. The lesson is geographic concentration plus speed: when change piles into the same zip codes and job ladders over a short span, social stability tilts. AI threatens a similar pattern, not because GPUs live in one valley, but because white-collar work is spatially clustered and organizationally standardized. Entire cohorts of early-career workers—those who would normally cycle through routine tasks to earn the next rung—risk facing ladders with the first steps sawn off.

That lost ladder matters more than any single layoff count. New AI-adjacent roles exist, but many demand credentials, domain expertise, and trust relationships that displaced workers do not yet have. Substitution arrives before complementarity scales. If you’ve ever tried to bridge that gap one training stipend at a time, you know how brittle the pipeline can be. Firms can promote a handful of “AI product managers” and “prompt engineers” while automating entire analyst pools. That math can make quarterly sense and still corrode the long run by starving the future of managers who learned judgment the slow way.

The weekend piece staged a clear debate and then quietly inverted it. On one side, Anthropic’s Dario Amodei and Ford’s Jim Farley have been blunt about white-collar displacement; on the other, Nvidia’s Jensen Huang and Meta’s Yann LeCun argue that productivity gains eventually expand headcount as throughput rises. Abramova didn’t try to referee who will be right in 2035. She pointed out that both can be “right” on different time horizons—and that the danger lives in the interval where efficiency gains are harvestable now and complementary demand takes years to catch up. The speed premium favors firms; the lag penalizes workers.

The management incentives are stark. If a model can process what used to be three teams’ worth of intake, the fastest way to monetize is to do the same volume with fewer people. The more imaginative path is to let humans keep the hard edges: judgment under uncertainty, client relationships, the messy seams between process maps. That “worker-augmenting” posture often skeptically reads as charity until one remembers what gets brittle when it’s cut away. Augmented teams accumulate tacit knowledge; fully automated flows propagate hidden failure modes. The cheapest quarter is not always the safest decade.

Policy, for once, has a clear direction even if the implementation is a trench fight. Retraining must be aggressive and properly funded, not as a press release but as a system with placement guarantees, employer buy-in, and on-ramps for people without elite credentials. Incentives should reward deployments where humans remain in the loop—responsible for decisions, not merely for supervising systems designed to make them optional. And guardrails are needed against the easiest value-capture move of all: declaring headcount reduction the north star of AI ROI. None of this is radical. All of it is urgent.

Ignore those levers and the downstream picture is familiar but sharper: widening inequality as high-credential roles compound advantage, persistent underemployment that saps participation rates, and a politics that treats institutions as saboteurs rather than buffers. The UK analogies are not about nostalgia; they are about what happens when disruption clusters faster than capacity builds. You can’t lecture stability into existence. You have to design for it.

Why did this particular warning become yesterday’s biggest story? Delivery and timing. A precise thesis, a usable timeline, historical memory, and a practical agenda—published where weekend readers actually are—beat the usual binary of “AI will add or cut jobs.” By centering pace, Abramova gave executives and policymakers a lever they can actually pull: stretch the shock. Sequence adoption so complementary roles scale alongside substitution. Tie tax incentives and procurement to augmentation commitments. Treat entry-level work as infrastructure, not overhead.

There is a version of the next decade where the headline “historic labor shock” ages into overcaution. That outcome would be a policy achievement, not a prediction error. The noise around AI has trained everyone to chase the biggest number—parameters, tokens, valuation. Yesterday’s story asked a more adult question: how much time will we buy for the people who make institutions work? The answer will not be found in a model card. It will be signed in budgets, org charts, and the first rungs of ladders we decide to rebuild.