The Year the “Automatable” Got a Raise

All year we told ourselves a simple story: AI aims for the office crowd first, and the office crowd should brace for impact. Then, as the lights flickered on the last trading week of the year, Vanguard quietly dropped a different plot. The jobs most exposed to AI aren’t shrinking back. They’re pulling ahead—on headcount and on pay.

This isn’t a blog post spun from vibes or an anecdote about some lucky prompt engineer. It’s a tidy slice of the labor market, measured across two timeframes—pre‑COVID 2015 to 2019, and the AI ramp from mid‑2023 to mid‑2025—run through a task‑level exposure model that maps what generative systems can plausibly automate or augment. On that map, about a hundred U.S. occupations sit closest to today’s AI blast radius: office clerks, HR assistants, data scientists, and their kin. If you expected a chalk outline, the numbers read like a twist ending.

The plot twist in the data

In the earlier period, those AI‑exposed roles grew at roughly 1.0% a year. During the last two years, their growth stepped up to 1.7%. The rest of the labor market slowed, down from 1.1% to 0.8%. Wages move the same way but louder: real pay in AI‑exposed roles barely budged pre‑COVID at 0.1%, then jumped to 3.8% in the recent window. Everyone else ticked up from 0.5% to 0.7%. For a group supposedly standing on the trapdoor, that’s a pretty sturdy floor.

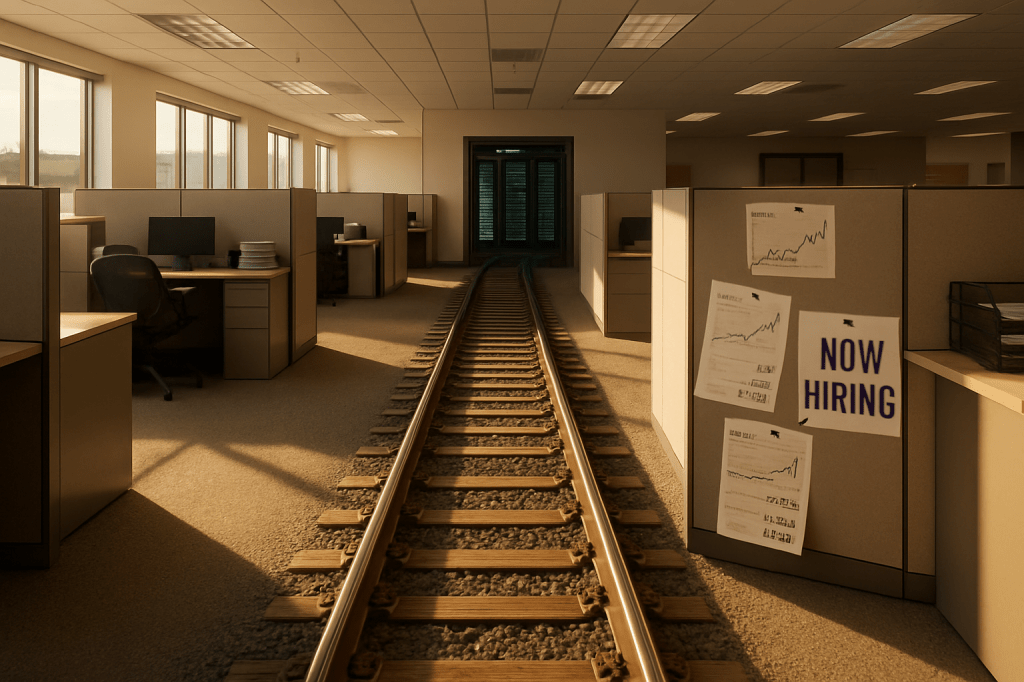

Vanguard calls AI a megatrend and places today’s infrastructure frenzy in the lineage of the railroads and the late‑’90s telecom build‑out. Think rows of GPUs where tracks or fiber once went, with the same logic underneath: when capital spends at industrial scale, labor markets bend in its direction—first where the tech can be productively paired with people.

Why the automation targets are getting paid

The earliest phase of a general‑purpose technology usually creates more complement than substitution. Firms don’t tear out entire job families while the tools are still learning the edges of reality. They reassign the repetitive strata of a role to the model and redirect the human into the messier stratum—judgment, context stitching, exception handling, persuasion. When that happens at scale, a job title doesn’t disappear; its composition shifts. Output per worker rises. And when output rises in tight, well‑capitalized teams, wages often follow.

Clerical work is a good example. The tasks that are quickest to automate—drafting boilerplate, formatting, summarizing—were never the reason those roles existed. They were the cost of doing the real work: moving a process forward and making sure nothing breaks. Put a model on the boilerplate and the clerk becomes a throughput manager. HR assistants aren’t just scheduling anymore; they’re orchestrating AI‑aided sourcing and compliance triage. Data scientists, meanwhile, become designers of decision systems rather than solo analysts. All of that is worth more to a firm than the previous task bundle. The wage data is what that revaluation looks like when you average it out.

The layoff headlines vs. the labor ledger

If your feed has been dominated by white‑collar layoffs, this feels like a contradiction. It isn’t. Cuts arrive in bursts and make news; work redesign shows up as quiet continuity with better throughput. Headline layoffs also confound causes—macro slowdowns, strategy resets, and AI all share the same press release. Zoom out to the ledger, and the net effect across exposed occupations points toward augmentation, not replacement, in the near term. Vanguard adds the obvious caution: models still struggle at the frontier of messy, real‑world decision‑making. That’s precisely the frontier where humans are parked, so widespread elimination hasn’t appeared in the data.

There’s another reconciliation: entry‑level friction. If you’re new to the market, it may feel harder to get a foothold. Vanguard attributes a lot of that to weak overall hiring rather than AI alone. But there’s also a structural shift embedded here. When a role gets augmented, the minimum viable human often needs to be more multi‑disciplinary—comfortable with tooling, measurement, and process design. That raises the bar in ways a macro series won’t capture cleanly yet.

Capital booms choose their winners

The analogies to railroads and the late‑’90s aren’t casual decoration. Massive build‑outs create a gravitational field. In the short run, the jobs that sit on the mainline of the build—those who specify, integrate, and supervise the new machinery—capture rents. In the late ’90s it was systems integrators and telecom engineers; in 2024–2025 it’s the teams wiring models into workflows and scaling them beyond demos. That advantage is fragile. If the capital cycle stutters—if “AI optimism” stalls in 2026, as Vanguard warns—the premium could narrow as quickly as it widened. The history of big tech booms rhymes: we lay the pipes first, the productivity arrives on a lag, and the market tests our patience in between.

The caveats are the map’s edges

This is an early snapshot, not a prophecy. Measurement choices matter. Mapping occupations to “AI‑exposed” tasks is necessary and imperfect, and the wage deflators we use can hide or overstate real gains. Composition shifts—who exits, who stays—can make an average look healthier than the lived experience of those in transition. And if models close some of their current gaps in judgment, the balance between complement and substitution can change fast. There’s no rule that says augmentation must be permanent.

Still, dismissing the signal entirely would be a mistake. Across two very different macro moments, the relative performance of AI‑exposed roles improved—not just in a frenetic quarter, but over a two‑year window as investment ramped. That suggests something more durable than a hype gust.

What this implies for 2026’s politics of work

We’re heading into a year where AI will be discussed as a jobs threat in every campaign speech. The new reality is more awkward: the jobs we expected to shrink are showing gains, while the broader market looks tepid. That will complicate the narrative. It also sharpens the policy question. If augmentation is the near‑term dominant mode, the bottleneck isn’t job supply; it’s transition capacity. The scarce resource becomes training that converts exposed workers into leveraged workers—people who can translate fuzzy business context into machine‑readable workflows and verify the outputs without drowning in oversight.

For employers, the takeaway is unromantic but urgent: don’t hoard the gains at the tool layer while starving the human layer that makes it pay off. The wage data hints that the firms getting it right are already rewarding the roles that sit closest to the model. For workers, the path is clearer than the headlines suggest. The tasks under threat are the ones you should hand to the machine. The value is in the interface—designing the prompts, the checks, the handoffs, the guardrails, and the judgment calls that keep the whole system honest.

Maybe the most surprising part of Vanguard’s note is how ordinary the mechanism is. When a general‑purpose technology arrives, the first people to benefit are the ones who stand between the new engine and the old processes. This time, those people weren’t wearing hard hats. They were the office crowd. And, for now at least, the automatable got a raise.