Jobs as Collateral: When the AI Boom Forgets to Ask If It Works

Yesterday’s front page carried an unusually sober idea for a market that has forgotten how to doubt. Yoshua Bengio, one of the architects of modern AI, warned there’s a “clear possibility that we will hit a wall.” The Guardian built an entire analysis around that sentence, and it landed with the weight of a balance sheet. Because this boom isn’t merely about faster chips or cleverer models. It is about a very specific promise: profitable work without the cost of human labor. Trillions in concrete, fiber, and GPUs have been justified on the expectation that software agents will do what entry‑ and mid‑career professionals do today, only cheaper, at scale, and without HR. If progress stalls, the wall isn’t just technical. It’s financial, and it’s employment.

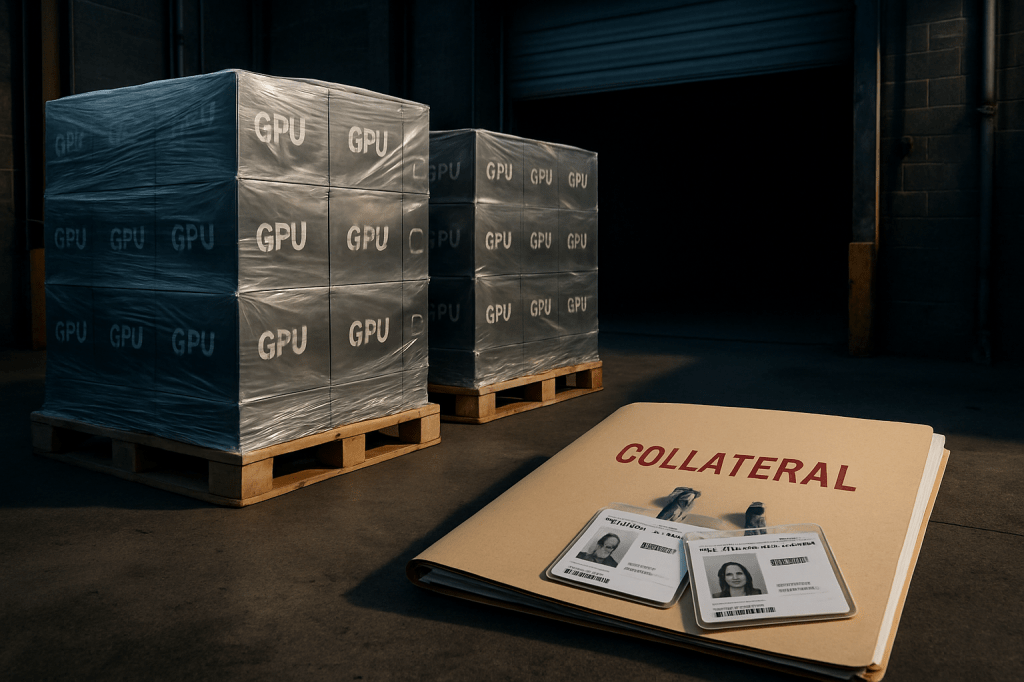

The wager under the warehouses

The capex number, repeated now across analyses, is astonishing: about $2.9 trillion in data centers through 2028. The equity market has priced that wager with equal conviction, concentrating roughly a third of the S&P 500’s value in AI‑linked names. It’s not just Big Tech’s cash flow carrying the load anymore. Private credit, high‑yield debt, and asset‑backed structures are bearing those racks on their shoulders. That financing stack only pencils out if the labor‑substitution thesis materializes—if models move from autocomplete to colleague, taking over tasks that bill at $50–$300 an hour across accounting, law, compliance, design, support, and the infinite backlog of white‑collar busywork.

Read that carefully: jobs are not only a downstream effect of AI progress; they are the collateral behind the infrastructure. Every server hall assumes a certain fraction of office work will be executed by machines. Every pension fund heavy on AI equities assumes those cost savings arrive on time. Every mezzanine facility rolled into a data‑center ABS assumes utilization and pricing that only make sense if digital labor displaces human labor at meaningful scale.

Two futures, both tough on careers

If AGI (or something close enough to it) keeps advancing, the corporate org chart snaps into a new shape. Output per employee climbs, but the ladder loses its lower rungs. Fewer analyst cohorts. Fewer junior associates. Fewer roles where people learn by doing and make the predictable mistakes that become judgment. Professional services turn into orchestration jobs: a smaller group of humans supervising fleets of agents, with mentorship outsourced to tooltips. Wages bifurcate. The apprenticeships that made mid‑career expertise possible start to thin out.

If progress hits Bengio’s wall, the damage doesn’t spare workers. Companies will have financed capacity built for labor savings that never quite show up. Utilization targets miss. Return assumptions compress. Credit tightens first in places most people don’t watch—data‑center lease securitizations, private credit covenants, high‑yield tech tranches—and then in places everyone does. Headcount plans are among the fastest levers when balance sheets feel that squeeze. You don’t need automated analysts to lose analyst seats; you just need an overbuild that has to be paid for. It’s the paradox of this moment: even without replacement, the anticipation of replacement can freeze hiring, delay backfills, and flatten wage growth.

What a “wall” looks like from inside a company

Hitting a wall isn’t an apocalyptic failure. It can look like incremental progress that’s too incremental, where each new model is better but not better enough to justify the capital already deployed. Agents that ace demos but stumble on unglamorous edge cases. Compliance review that still needs a person. Accounting that still needs reconciliation. Legal drafting that still needs a lawyer to avoid costly mistakes. If the delta between “almost” and “trustworthy” remains stubborn, the economics of substitution don’t close; augmentation helps, but augmentation alone can’t amortize $2.9 trillion.

Inside HR and finance, the misalignment shows up in deceptively simple ratios: how many seats can one human supervise once agents take over routine tasks? How many client matters can the team handle at a given service level? If those numbers come in under the deck, the hiring plan changes long before the technology does. The irony is brutal—people get held in place while the company waits for software that still needs them.

When employment is a macro variable, not a management choice

The Guardian piece reframed something veterans of this space have felt intuitively. The AI capex wave has turned white‑collar employment into a macro variable. This isn’t a firm‑by‑firm efficiency project anymore; it’s a system‑wide bet whose payoff depends on replacing expensive human time. Because the market has priced the payoff in advance, disappointment travels through credit spreads and equity drawdowns before it shows up as a product miss. That feedback loop feeds directly into job postings, compensation bands, and promotion cycles.

The uncomfortable symmetry

Whether AGI arrives on schedule or collides with its limits, the near‑term story for workers converges on the same conclusion: fewer openings where careers begin. In the success path, machines take the routine work that once justified junior roles. In the stall path, the financial overhang squeezes budgets as if the substitution had happened, even if humans are still doing the work. Different mechanisms, similar outcomes. The middle of the org chart becomes narrower; the entrance becomes smaller.

For an audience that already knows what “AI disruption” means, the novelty here isn’t the technology. It’s the accounting. Yesterday’s warning wasn’t about parameters or tokens. It was about the intimacy between model capability and the cost of human time. The market has already spent tomorrow’s labor savings. Now we find out if the future can afford the bill.