Meta’s $600 Billion Bet Turns AI Into an American Jobs Story

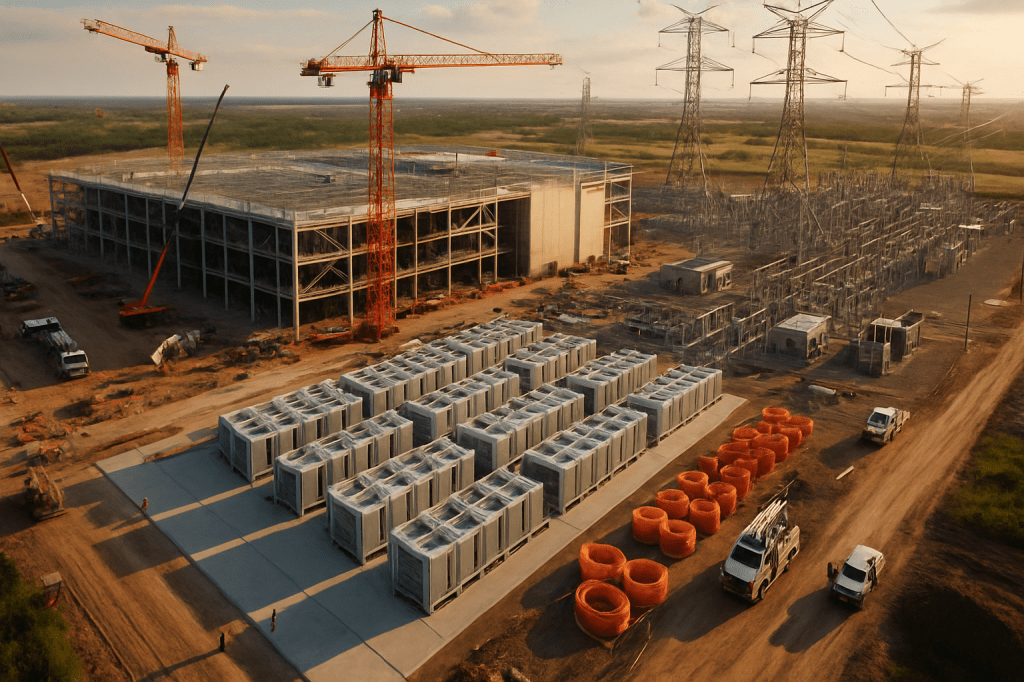

The announcement didn’t land like a product demo or a research paper. It sounded more like a groundbreakers’ roll call. Meta says it will invest $600 billion in U.S. AI infrastructure by 2028, and it’s not shy about the framing: this is an employment and local-economy play as much as a compute strategy. The shift is subtle but profound. For two years, AI’s public narrative has centered on models, benchmarks, and the specter of white-collar automation. Now, the world’s most aggressive spender in AI is telling mayors, contractors, and utility commissions that the next wave of intelligence will be poured, welded, and wired into place.

On paper, the plan reads like a set of financial line items—company-owned data centers, third-party cloud commitments, and compensation for AI talent. In practice, it is a massive logistics operation with labor at its core. Meta points to a track record: data center projects since 2010 have supported more than 30,000 skilled-trade construction roles and 5,000 ongoing operations jobs, and the company says it is already routing more than $20 billion to subcontractors across steel, electrical, piping, fiber, and other trades. That is the overture. The symphony is the next three years of build-out, scaled to a number that forces change not just inside Meta but across the American workforce.

From algorithms to earthmovers

AI got good before it got physical. The last breakthroughs were downloadable: models scaling across cloud clusters, inference sliding into apps. The $600 billion era is different. It has a smell—of cut concrete, oiled cable, and transformer varnish. It occupies land, so it requires land-use approvals. It draws power, so it must be negotiated with utilities that move at civilizational speed. And it takes hands—many of them—to bring it online.

That’s why Meta’s finance team is telegraphing not just bigger capex but capex that accelerates, with 2026 outpacing 2025 and total expenses rising significantly faster. Acceleration in physical infrastructure has a distinct labor signature: hiring ramps for electricians, pipefitters, and fiber techs; vendor backlogs tighten; wages nudge up where capacity is constrained; apprenticeships swell. AI, long discussed as a force flattening white-collar hierarchies, is about to stress-test America’s skilled trades pipeline instead.

Two labor markets, one firehose

There are really two employment stories braided together here. The first is a surge in blue-collar demand tied to construction and commissioning. These are jobs with locality—if Meta builds near you, you feel it. They are also jobs with sequencing: foundation, frame, steel, electrical, cooling, fiber, testing. The second story stretches across office parks and research labs: compensation for AI specialists is already a strategic lever, and Meta is signaling it will keep turning it. The build phase will mint overtime for union halls while executive recruiters negotiate commas in machine learning offers. It’s not either-or; it’s both, and the friction between them—constrained supply in trades and talent—will define the price of delivery.

This duality affects more than payroll. It redistributes negotiating power. Towns that have watched warehouses roll in and roll out without lasting prosperity now have leverage; data centers are stickier assets with heavier interconnects and deeper vendor ecosystems. Workers who once weighed a move for a refinery turnaround may compare offers for multi-year data center projects with cleaner working conditions and more predictable schedules. AI researchers who thought a change of employer meant a change of badge may instead find themselves embedded in vendor networks that sit between hyperscalers and the grid.

The vendor economy gets its own upgrade

Meta’s current $20 billion flow to subcontractors is an early indicator of where the multiplier effects land. If the company executes even half the planned build-out on schedule, third-party service providers will feel like they’ve been handed a firehose. The immediate winners aren’t just the big general contractors; they’re the regionally dominant specialists with the right certifications and crews to keep a build sequence on pace. Supply constraints become policy issues—transformers, switchgear, high-capacity fiber—and every bottleneck spurs either domestic expansion or creative sourcing. In other words, meta-AI growth begets meta-manufacturing and logistics decisions, many of them made by suppliers who have never seen their work discussed on an earnings call.

Power, water, and the politics of permission

Infrastructure is never only concrete and code. It is also permission. A program of this scale will negotiate with the grid as if it were a cofounder. Power availability and interconnect timelines will quietly decide which communities become AI hubs and which become waystations. Water usage and heat management—less glamorous than model weights, more decisive than most people realize—will shape local sentiment. Some municipalities will trade incentives for promises of long-term operations jobs. Others will demand investments in training pipelines and community benefits. The jobs narrative isn’t just moral framing; it’s procurement strategy. It buys time with permitting boards and patience with neighbors.

After the ribbon-cutting

Construction jobs swell and recede; operations endure. Meta’s own data—thousands of ongoing roles after build—suggests a slimmer but stable workforce maintaining facilities where uptime is sacred. These jobs don’t look like the myth of the endlessly shrinking tech back office. They look like reliability engineering, plant ops, on-site security, facilities automation, and the specialized technicians who keep high-density compute cold and connected. The trade-off is familiar to any industry town: a boom in build, a plateau in run, and the need to convert temporary opportunity into durable advantage through training and supplier development.

The broader labor shock

Why did this story dominate the week’s conversation about AI and employment? Scale converts abstractions into plans. “At least $600 billion” is not a pilot; it is a commitment window inside which manufacturers expand shifts, unions bargain new clauses, community colleges rewrite syllabi, and local governments revisit zoning maps. It is also a signal to competitors and partners that the bottleneck in AI is no longer just algorithmic. It is physical throughput—power lines, concrete pads, fiber routes—and the human hands that make throughput real.

For workers who have spent two years reading about AI as a threat to their desk, this is the counterfactual arriving in hard hats. For workers who never thought AI had anything to do with them, it’s the forecast that their wages might rise because the future suddenly needs what they know. For executives who thought AI meant trimming staff, it’s a reminder that the competitive frontier may be constrained less by storyboards and more by whether you can find enough electricians to close a panel and pass inspection.

Signals to track next

If Meta is right that expenses will rise significantly faster as the build accelerates into 2026, the proof will show up in a few places: the cadence of new site announcements; booking spikes for regional contractors; longer lead times for critical electrical components; wage moves in trades across hot geographies; and a quieter but telling metric, apprenticeship enrollments where data center clusters form. Inside the company and its ecosystem, watch for compensation drift and the gravitational pull that top-tier AI packages exert on both startups and incumbents.

AI was supposed to vaporize work or at least displace it into the cloud. Meta’s plan reframes the near future: intelligence at scale is heavy, local, and staffed. If the company delivers on even a large fraction of this commitment, the labor market over the next three years won’t look like the glossy automation slides. It will look like cranes on the skyline, backlog boards at the union hall, and a quiet battle for the people who can wire the future as fast as the models can learn.