On Day One of 2026, Hiring AI Got New Rules—and New Accountability

Some policy turns feel symbolic. This one redraws the floor plan. When the calendar rolled to January 1, the systems that screen résumés, rank candidates, score interviews, and nudge performance reviews woke up to a new reality: outcomes now carry legal weight in Illinois, and intent now has an enforcer in Texas. The debate over whether AI shapes who works where stopped being a forecast and became infrastructure.

Illinois makes outcomes the liability

Illinois did not tinker at the margins. By amending its Human Rights Act through HB 3773, the state put employers on the hook for what their AI does, not what they meant it to do. If an automated tool used in recruitment, hiring, promotion, discipline, discharge, or any other employment decision produces discriminatory effects against protected classes, that is a civil-rights violation—even if nobody set out to discriminate. Alongside that impact standard, Illinois demands disclosure when AI is used and takes aim at proxy variables like ZIP code that smuggle protected traits through the back door.

This flips the power dynamic inside HR tech stacks. Third-party vendors can no longer hide behind glossy benchmarks if the results tilt the wrong way. Employers can’t plead ignorance when features correlate with race or disability through geography or history. The act converts “bias audits” from a marketing line into a survival tool: document the model, justify the features, measure the outcomes, and be prepared to show your work. A compliance spreadsheet won’t cut it; Illinois is asking for evidence that people, not proxies, are driving decisions.

Texas redraws the perimeter and hands out a whistle

Texas chose a different instrument with its Responsible Artificial Intelligence Governance Act. The statute is narrower than early drafts, but it lands where it matters for employment: no developing or deploying AI for discriminatory purposes, plus new disclosure and investigative powers for the Attorney General. And it stands up an AI sandbox—bureaucratic jargon, yes, but consequential for how vendors test and iterate systems that ultimately touch hiring and evaluation.

If Illinois is about outcomes, Texas is about oversight. The AG becomes a new character in the hiring workflow, capable of asking, “What did you build, how did you test it, and why did you deploy it here?” Companies that operate in Texas or sell into it don’t need to guess whether employment-adjacent tools fall inside scope; the chilling effect alone shifts roadmaps. The sandbox also creates a proving ground where responsible-by-design claims can be tested against reality rather than sales decks.

The operational shift started yesterday

HR leaders did not get a grace period. The practical to-do list arrived with the laws: inventory every automated decision system that touches a job seeker or employee, issue or update notices, interrogate vendors, and remove features with proxy risk. But the change is deeper than a policy update. Illinois’ impact standard pushes organizations to monitor downstream results continuously, not just at procurement. Texas’ enforcement posture forces documentation of purpose and process at the moment of design, not after headlines.

And this is not happening in a vacuum. California’s FEHA regulations already extended anti‑discrimination duties to automated systems last fall. New York City’s AEDT rules are on the books, even as the comptroller calls out weak enforcement. Colorado’s high‑risk AI law arrives mid‑year. Alone, each regime is manageable. Together, they function like a national regime by multiplication: multi-state employers will standardize to the strictest common denominator, reshaping the products they buy and the models they permit in production.

What changes inside the machines

When liability attaches to outcomes, model design choices are no longer aesthetic. Feature sets that once boosted accuracy by a fraction now carry legal voltage. ZIP code is the obvious casualty, but so are its cousins: commute distance, school clusters, even convenience features that encode neighborhood. Expect a move toward constrained models, auditable transformations, and reason codes that make sense to a regulator as well as a data scientist. The “black box” era was already fading in hiring; Illinois accelerates the exit.

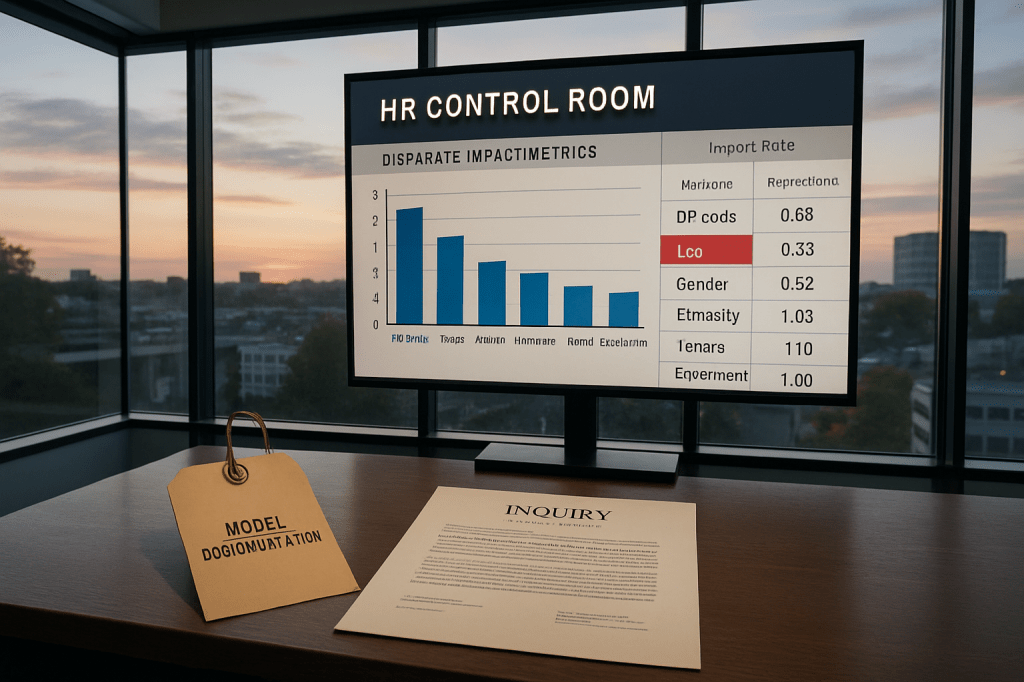

Evaluation culture will change, too. Static pre‑deployment audits give way to live dashboards tracking disparate impact over time, triggers for retraining when demographics shift, and contract clauses that obligate vendors to surface drift. The most valuable artifact in 2026 may be something nobody shipped in 2025: evidence of non‑discrimination, preserved and replayable. Startups that treated fairness as a slide will feel the air thin; vendors that can prove fitness on demand just gained pricing power.

The stakes are not abstract

It is tempting to file this moment under “compliance,” but the frame is civil rights, not paperwork. Illinois’ move says the harm is the outcome; Texas’ says there is someone watching the intent. Put together with California, New York City, and Colorado, the message is unmistakable: automated hiring and evaluation are no longer just a tech choice. They are a regulated space where design decisions decide who gets seen, who gets scored, and who never hears back.

For an industry that has thrived on speed, the adjustment will feel like friction. For workers who live downstream of models, it may feel like oxygen. And for anyone building AI for the workplace, January 1 should recalibrate the definition of “done.” In Illinois, deployment without demonstrably equitable outcomes is unfinished work. In Texas, deployment without a story you can defend to an investigator is unfinished work. That is not a slowdown; it is the cost of bringing automation into decisions that shape a life.